Since the earliest beginnings of geological inquiry, the classification and nomenclature of sedimentary sequences from Earth history’s most recent period has been to some extent problematic. During the first two decades of the nineteenth century the unconsolidated sediment that rested unconformably on Tertiary rocks, capped hills, and frequently contained exotic clasts and the remains of animals, many of which are still extant, was considered a product of the Biblical Flood (the ‘Diluvial Theory’). This origin for the ‘Diluvium’ as it was called was accepted by most eminent geologists of the time, including Buckland and Sedgwick.

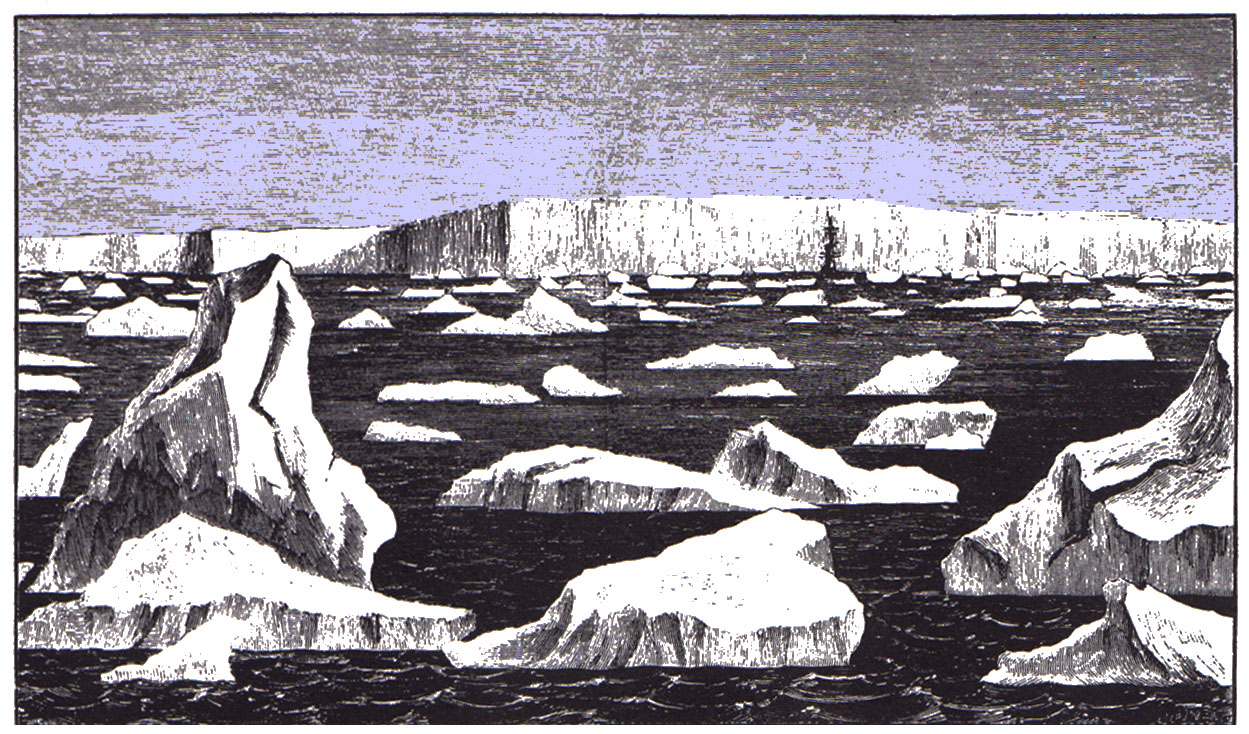

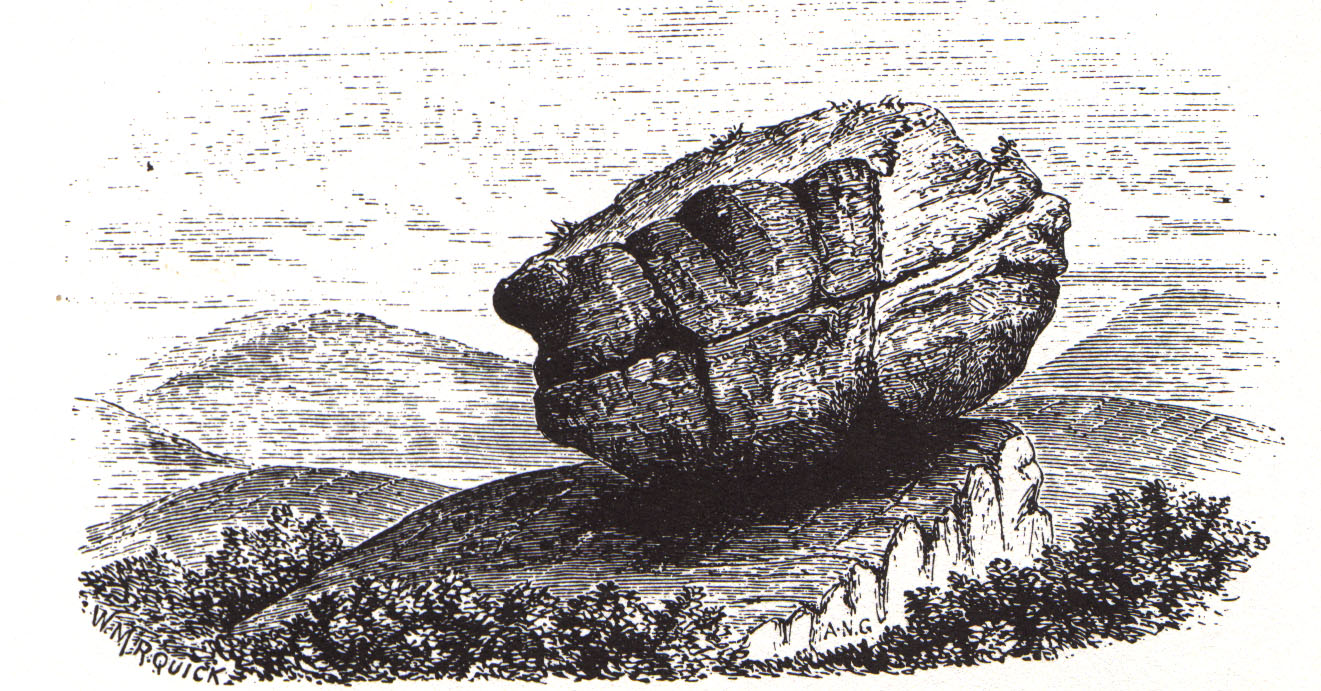

A vindication of this view was suggested at much the same time by observations reported from the voyages of exploration of the polar regions where floating ice had frequently been seen transporting exotic materials. Acceptance of this process as an explanation for the transport of erratic clasts, even to the tops of the highest hills, reinforced the Diluvial Theory, leading to adoption of the term ‘drift’ to identify the sediment. This theory was very much the accepted explanation until the mid-nineteenth century. However, geologists working in the Alps and northern Europe had been struck by the extraordinary similarity of the ‘drift’ deposits and their associated landforms to those being formed by modern mountain glaciers. Several observers such as Perraudin, Venetz-Sitten, de Charpentier and others proposed that the glaciers had formerly been more extensive, but it was the palaeontologist Agassiz who first advocated that this extension represented a time that came to be termed the Ice Age by Goethe.

Quaternary versus Pleistocene

After having convinced Buckland and Lyell of the validity of his Glacial Theory in 1840 Agassiz’s ideas became progressively accepted. The term Drift became established for the widespread sands, gravels and boulder clays thought to have been deposited by glacial ice. Meanwhile, Lyell had already proposed the term Pleistocene in 1839 for the post-Pliocene period closest to the present.

Lyell defined the Pleistocene period on the basis of its molluscan faunal content, the majority of which are still extant. However, the term Quaternary (Quaternaire or Tertiaire récent) had already been applied in 1829 by Desnoyers for marine sediments in the Seine Basin (Bourdier 1957, p.99), and this the term had been in use since the late 18th century. The term originates from G. Arduino (1714-1795) who distinguished four separate stages or ‘orders’ which he said were very large strata arranged one above the other. These four ‘orders’ were Primary, Secondary, Tertiary comprising the Atesine Alps, the Alpine foothills, the sub-Alpine hills and ‘the forth order’, comprising the Po plain area, respectively (Schneer 1969).

Several texts state that it was Adolphe Morlot (1820-1867) who first coined the term ‘Quaternary’. In fact there were earlier usages, with different meanings. According to Marianne Klemun (Universität Wien, Austria), Adolphe von Morlot, working in Bern, Switzerland, further contributed to the establishment of the concept ‘Quaternär‘ (1854). Her paper discusses the range of the terms’ meaning during the early phase of its introduction and development, in order to give and appropriate categorization of Morlot’s specific contribution and the reason why he introduce the term Quaternär. The discussion is based to a considerable extent on correspondence between Morlot and Friedrich Simony (1813-1896) of Vienna University.

Both terms Quaternary and Pleistocene thus existed in parallel, one or the other having been proposed to be dropped periodically ever since. Moreover, both have become synonymous with the Ice Age and also the period during which humans appear. However, the Quaternary was different from the Pleistocene in that it also included Lyell’s original ‘Recent’, later named Holocene by the International Geological Congress in 1885. The term Holocene was originally defined by Gervais (1867-9) “for the post-diluvial deposits approximately corresponding to the post-glacial period” (Bourdier 1957, p.101). This period was originally considered to follow the Quaternary instead representing a fifth era or Quinquennaire (Parandier 1891) but this division was deemed to be “excessive” (Bourdier 1957, p.101). Further terminological history can be found in Bourdier (1957) and de Lumley (1976).

Questions concerning periodisation in geology are obviously still with us, and the same goes for the relationships of time, change and discontinuity. The fact that such questions are debated repeatedly in both history and geology is illustrated by the extensive discussion in recent years about the use of the term ‘Quaternary’ as a stratigraphic unit. Thus periodisation is not merely a philosophical issue. Neither does it belong solely to the sociology or politics of science. Rather it must be seen as an essential instrument and an integral part of an on-going discussion of fundamental ideas about time in general.

The geologist, Giovanni Arduino (1714 – 1795) was one of the founders of stratigraphy and established the bases of the stratigraphical chronology, using the various geological characteristics of the layers.

The geologist, Giovanni Arduino (1714 – 1795) was one of the founders of stratigraphy and established the bases of the stratigraphical chronology, using the various geological characteristics of the layers.

His work is presented in the ‘Two letters over several directed natural observations’. In the letter he wrote to Professor A.Vallisneri the younger on 30 March 1759 Arduino proposed a classification into four great ‘orders’; Primary, Secondary, Tertiary and Quaternary . Click image to enlarge. Image below from F. Ellenberger 1994 Histoire de la Géologie. Tome 2. Technique et documentation (Lavoisier) Paris.

The pages shown are taken from the original publication by Jean Desnoyers (1829) in which he uses the term Quaternaire for the first time to apply to the ‘recent Tertiary’ deposits in the Paris Basin.

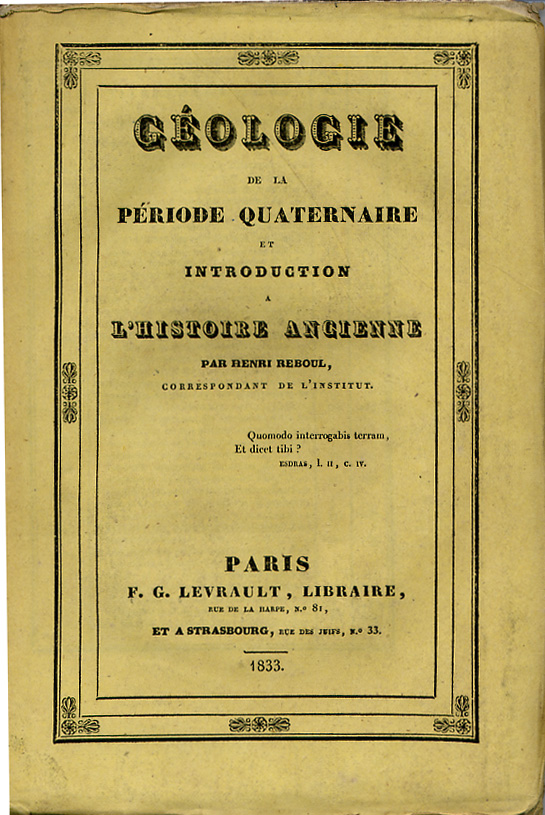

The cover shown is from a review of the Geology of the Quaternary Period by Henri Reboul, published in Paris in 1833. On p.1-2 he states that the Quaternary “concerns those terrains characterised by animal and plant species that resemble those that are living today in the same places”.

Summary

Therefore the classification determined by historical priority and long usage is:

Cenozoic Erathem / Era

Quaternary (Anthropogene) System / Period

Holocene Series / Epoch

Pleistocene Series / Epoch

Many consider that the Quaternary is not a satisfactory term in the scheme; Primary and Secondary have been replaced by Palaeozoic and Mesozoic respectively, and Tertiary has been replaced by Palaeogene and Neogene as formal systems within the Cenozoic, so the alternative Anthropogene (often in use in the ex-USSR), has been proposed. A further term Pleistogene was proposed by Harland et al. (1989) in the Geological Time Scale, although thought to fit better the overall nomenclature, it has never found favour. However, tradition prevails with the continued use of the Quaternary and is accepted here. Alternative scales have been proposed (e.g. to include the Pleistocene in the Neogene). An analogous proposal has been made to include the Holocene as a Pleistocene stage (cf. the Flandrian: see below). Although both would undoubtedly be logical developments, they run counter to history and to an immense literature, and ultimately would serve no great purpose.

According to Nilsson (1983 The Pleistocene. Reidel, Dordrecht, p. 23-4), Soviet scientists discarded the concept of an integrated Tertiary Period. They followed certain non-Russian writers in classifying the divisions Paleogene and Neogene as periods, which they divided into the conventional epochs. Being (as they saw it) a relic of an antiquated classification, the term Quaternary, too, had been abandoned and replaced by the designation Anthropogene (analogous to Paleogene, Neogene), though its conceptional meaning remained unaltered (cf. i.a. Gerasimov, I.P. 1979 Anthropogene and its major problem. Boreas 8, 23-30.). The Quaternary or Anthropogene retained the rank of a period. Linguistically, however, the term Anthropogene seems less fortunate.

With similar motivation, Czechoslovakian geologists used the term Anthropozoikum as a synonym for Quaternary. Procedures of this kind clearly over-emphasise the significance of the changes that serve to distinguish the Quaternary.

Holocene (or Flandrian)

Holocene is the name for the most recent interval of Earth history and includes the present day. It is generally regarded as having begun 10 000 radiocarbon years or the last 11,500 calibrated (i.e. calender) years before present (i.e. 1950). The term ‘Recent’ as an alternative to Holocene is invalid and should not be used. Sediments accumulating or processes operating at present should be referred to as ‘modern’ or by similar synonyms.

The term Flandrian, derived from marine transgression sediments on the Flanders coast of Belgium (Heinzelin & Tavernier, 1957), has often been used as a synonym for Holocene. It has been adopted by authors who consider that the last 10 000 years should have the same stage-status as previous interglacial events and thus be included in the Pleistocene. In this case, the latter would thus extend to the present-day (cf. West 1968; 1977, 1979; Hyvärinen 1978). This usage, although advocated particularly in Europe, has been loosing ground in the last two decades (cf. Lowe & Walker 1997, p.16).

References

Bourdier, F. 1957 Quaternaire. In: (Pruvost, P. ed.) Lexique stratigraphique international. Vol. 1 Europe. 99- 100, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique: Paris.

Desnoyers, J. 1829. Observations sur un ensemble de dépôts marins.. Annales des Sciences naturelles (Paris), 171-214, 402-491.

Gervais, P. 1867-9 Zoologie et paleontologie générales. Nouvelles recherches sur les animaux vertétebrés et fossiles . Paris, 263pp.

Harland, W.B., Armstrong, R.L., Cox, A.V., Craig, L.E., Smith, A.G. & Smith, D.G. 1989. A geologic time scale . Cambridge University Press, 263 pp.

Heinzelin, J. de & Tavernier, R. 1957 Flandrien. In: (Pruvost, P. ed.) Lexique stratigraphique international. Vol. 1 Europe. 32, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique: Paris.

Hyvärinen, H. 1978 Use and definition of the term Flandrian. Boreas 7, 182.

Lowe, J.J. & Walker, M.J.C. 1997: Reconstructing Quaternary environments. 446pp. Longmans, London.

Lumley, H. de 1976 La Préhistoire Française . Editions CNRS: Paris, Tome 1, 5-23..

Lyell, C. 1839. Nouveaux éléments de Géologie . Paris: Pitois-Levrault, 648pp.

Parandier, H. 1891 Notice géologique et paléontologique sur la nature des terrains traverses par le chemin de fer entre Dijon et Châlons-sur-Saône. Bulletin de la Société géologique de France, series 3, 19, 794-818.

Reboul, H. 1833 Géologie de la période Quaternaire et Introduction à l’histoire ancienne. Paris: F.G.Levrault, 222pp.

Schneer, C.J. 1969. Introduction. In: (Schneer, C.J. ed.)Towards a history of Geology. 1-18. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press: Cambridge and London, 469pp.

West, R.G. 1968. Pleistocene geology and biology, first edition Longmans Green, London.

West, R.G. 1977: Pleistocene geology and biology, second edition. Longmans, London.

West, R.G. 1979 Further on the Flandrian. Boreas 8, 126.

Extract from: Gibbard, P.L. & van Kolfschoten, Th. 2005 The Quaternary System. (The Pleistocene and Holocene Series). 441-452. In: Gradstein, F. Ogg, J. & Smith, A. (eds) A Geologic Time Scale 2004. Cambridge University Press 589 pp.