Climatostratigraphy

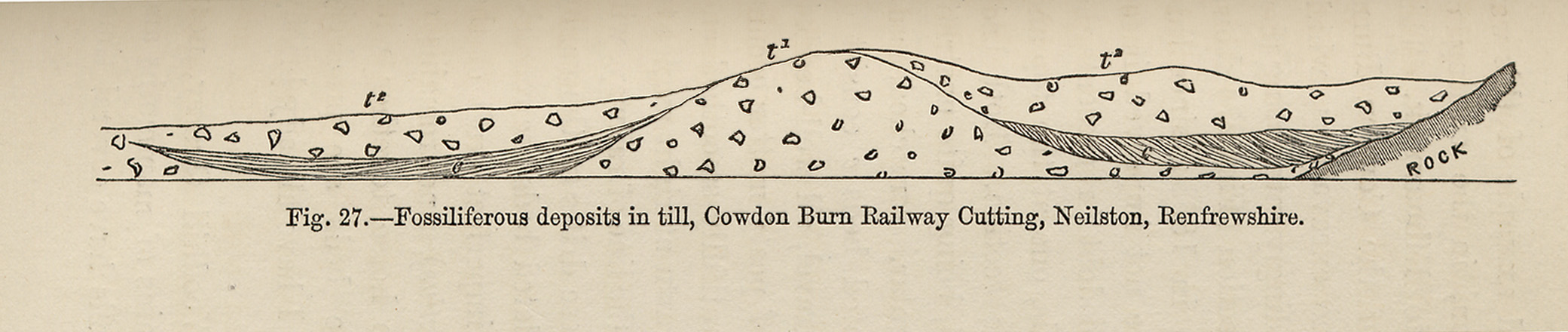

In contrast to the rest of the Phanerozoic, the Quaternary has a long-established tradition of sediment sequences being divided on the basis of represented climatic changes, particularly sequences based on glacial deposits in central Europe and mid-latitude North America. This approach was adopted by early workers for terrestrial sequences because it seemed logical to divide till (glacial diamicton) sheets and non-glacial deposits or in stratigraphical sequences into glacial (Glaciation) and interglacial periods respectively (cf. West, 1968, 1977; Bowen 1978). In other words the divisions were fundamentally lithological (Fig. 1). The overriding influence of climatic change on sedimentation and erosion in the Quaternary has meant that, despite the enormous advances in knowledge during the last century and a half, climate-based classification has remained central to the subdivision of the succession. Indeed the subdivision of the modern ocean sediment isotope stage sequence is itself based on the same basic concept. It is this approach which has brought Quaternary geology so far, but at the same time causes considerable confusion to workers attempting to correlate sequences from enormously differing geographical and thus environmental settings. This is because of the great complexity of climatic change and the very variable effects of the changes on natural systems.

Fig. 1 Fossiliferous sand deposits between tills exposed in the Cowden Burn railway cutting at Neilston in Renfrewshire, Scotland, from Geikie (1874; Fig. 27).

Penck and Brückner

The recognition of climatic events from sediments is an inferential method and by no means straightforward. Sediments are not unambiguous indicators of contemporaneous climate, so that other evidence such as fossil assemblages, characteristic sedimentary structures (including periglacial structures) or textures, soil development and so on must be relied upon wherever possible to illuminate the origin and climatic affinities of a particular unit. Local and regional variability of climate complicates this approach in that sequences are the result of local climatic conditions, yet there remains the need to equate them with a global scale. For at least the first half of the 20th century the preferred scale was that developed for the Alps at the turn of the century by Penck & Brückner (1909-11) (Fig. 2, 3). In recent decades it has been replaced by the marine or ice-core oxygen isotope record.

For the Alps the sequence in increasing age, with later additions, is:

Würm – Glacial – (Würmian) Riss/Würm – Interglacial Riss – Glacial – (Rissian) Mindel/Riss – Interglacial Mindel – Glacial – (Mindelian) Günz/Mindel – lnterglacial Günz – Glacial Donau/Günz – Interglacial Donau – Glacial ?Biber – Glacial

Fig. 2 Sketch longitudinal sections through the gravel district of the northern Alpine Foreland of southern Germany showing the distributon of glaciofluvial sediments and their relationship to end-moraines of alpine glaciations by Albrecht Penck. These units are those upon which the original Alpine classification was based. From Penck & Brückner (1909; Table 1). Click on image to see full version of illustration.

Fig. 3 The geologists Eduard Brückner (l) and Albrecht Penck (r) with the title page of the first volume of their classic book ‘Die Alpen im Eiszeitalter’ (1909-11).

Modern divisions

Since the mid-20th century a comparable scheme developed in northern European has been dominant, at least in Europe, but similar schemes were established elsewhere, such as North America, or the former USSR. More recently, these schemes have tended to be replaced by the marine isotope record (Bowen 1978). Today the burden of correlation lies in equating local, highly fragmentary, yet high-resolution terrestrial and shallow marine sediments on the one hand, with the potentially continuous, yet comparatively lower resolution ocean isotope sequence on the other.

Before the impact of the ocean-core isotope sequences an attempt was made to formalise the climate-based stratigraphical terminology in the American Code of Stratigraphic Nomenclature (1961) where so-called geologic-climate units were proposed. Here a geologic-climate unit is based on an inferred widespread climatic episode defined from a subdivision of Quaternary rocks (American Code 1961). Several synonyms for this category of units have been suggested, the most recent being climatostratigraphical units (Mangerud et al. 1974) in which an hierarchy of terms is proposed. In subsequent, stratigraphic codes, however (Hedberg, 1976; North American Commission on Stratigraphic Nomenclature, 1983; Salvador, 1994), the climatostratigraphic approach has been discontinued since it has been considered that for most of the geological column ‘inferences regarding climate are subjective and too tenuous a basis for the definition of formal geologic units’ (North American Commission, 1983, p 849). This view does not find favour with Quaternary scientists, however, since it is therefore difficult to envisage a scheme of stratigraphic subdivision for recent earth history that does not specifically acknowledge that fact (Lowe and Walker, 1997). Accordingly, Quaternary stratigraphical sequences continue to be divided into geologic-climatic units based on proxy climatic indicators, and hence following with this approach, the Pleistocene/Holocene boundary (the base of the Holocene Series/Epoch) for example, is defined on the basis of the inferred climatic record. Boundaries between geologic-climate units were to be placed at those of the stratigraphic units on which they were based.

The American Code (1961) defines the fundamental units of the geologic-climate classification as follows:

- A Glaciation is a climatic episode during which extensive glaciers developed, attained a maximum extent, and receded. A Stadial (‘Stade’) is a climatic episode, representing a subdivision of a glaciation, during which a secondary advance of glaciers took place. An Interstadial (‘Interstade’) is a climatic episode within a glaciation during which a secondary recession or standstill of glaciers took place.

- An Interglacial (‘Interglaciation’) is an episode during which the climate was incompatible with the wide extent of glaciers that characterise a glaciation.

In Europe, following the work of Jessen & Milthers (1928), it is customary to use the terms interglacial and interstadial to define characteristic types of non-glacial climatic conditions indicated by vegetational changes; interglacial to describe a temperate period with a climatic optimum at least as warm as the present interglacial (Holocene, Flandrian: see below) in the same region, and interstadial to describe a period that was either too short or too cold to allow the development of temperate deciduous forest or the equivalent of interglacial-type in the same region (West 1977). Lüttig (1965) also recognised this problem and attempted to avoid the glacial connotations by proposing the terms cryomer and thermomer for cold and warm periods respectively. These terms have found little acceptance, however.

In North America, mainly in the USA, the term interglaciation is occasionally used for interglacial (cf. American Code 1961). Likewise, the terms stade and interstade may be used instead of stadial and interstadial, respectively (cf. American Code 1961). The origin of these terms is not certain but the latter almost certainly derive from the French language word stade (m) which is unfortunate since in French stade means (chronostratigraphical) stage (cf. Michel et al. 1997), e.g. stade isotopique marin = marine isotope stage.

It will be readily apparent that, although in longstanding usage, the glacially-based terms are very difficult to apply outside glaciated regions. Moreover, as Suggate and West (1969) recognised, the term Glaciation or Glacial is particularly inappropriate since modern knowledge indicates that cold rather than glacial climates have tended to characterise the periods intervening between interglacial events over most of the earth. They therefore proposed that the term ‘cold’ stage (chronostratigraphy) be adopted for ‘glacial’ or ‘glaciation’. Likewise they proposed the use of the term ‘warm’ or ‘temperate’ stage for interglacial, both being based on regional stratotypes. The local nature of these definitions indicates that they cannot necessarily be used across great distances or between different climatic provinces (Suggate and West 1969; Suggate, 1974; West, 1977) or indeed across the terrestrial / marine facies boundary (see below). In addition it is worth noting that the subdivision into glacial and interglacial is mainly applied to the Middle and Late Pleistocene.

Perhaps the biggest problem with climate-based nomenclature is where the boundaries should be drawn. Ideally they should be placed at the climate change but since the events are only recognised through the responses they initiate in depositional or biological systems a compromise must be agreed. As Bowen (1978) emphasises there are many places at which boundaries could be drawn but in principle they are generally placed at mid-points between temperature maxima and minima, e.g. in ocean sediment cores. This positioning is arbitrary but is necessary because of the complexity of climatic changes. However, problems may arise when attempts are made to determine the chronological relationship of boundaries drawn in sequences of differing temporal resolution or sediment facies, and indeed determined using differing proxies. By contrast in temperate Northwest Europe the base of an interglacial or interstadial is very precisely defined. It is placed at the point where herb-dominated (cold-climate) vegetation is replaced by forest. The top (i.e. the base of the subsequent glaciation or cold stage) is drawn where the reverse occurs (Jessen & Milthers 1928; Turner and West 1968). It is unclear, however, how this relates to the timing of the actual climate change recorded or how this is recorded by other proxies.

In the second half of the 20th century, it was a recognised that Quaternary time should be subdivided as far as possible in keeping with the rest of the geological column using time, or chronostratigraphy, as the basic criterion (e.g. van der Vlerk 1959; Gibbard & West 2000). Because stages are the fundamental working units in chronostratigraphy they are considered appropriate in scope and rank for practical intraregional classification (Hedberg, 1976). However, the definition of stage-status chronostratigraphical units, with their time – parallel boundaries placed in continuous successions wherever possible, is a serious challenge especially in terrestrial Quaternary climate-dominated sequences. In these situations boundaries in a region may be time-parallel but over greater distances problems may arise as a result of diachroneity. It is probably correct to say that only in continuous sequences which span entire interglacial – glacial – interglacial climatic cycles can an unequivocal basis for the establishment of stage events using climatic criteria be truly successfully achieved. There are the additional problems which accompany such a definition of a stage, including the question of diachroneity of climate changes themselves and the detectable responses to those changes. For example, it is well known that there are various ‘lag’-times of geological responses to climatic stimuli. Thus, in short, climate-based units cannot be the direct equivalents of chronostratigraphical units because of the time-transgressive nature of former. This distinction of a stage in a terrestrial sequence from that in a marine sequence should be remembered.

In general practise today these climatic subdivisions have been used interchangeably with chronostratigraphical stages by the majority of workers. Whilst this approach, which gives rise to alternating ‘cold’ and ‘warm’ or temperate’ stages, has been advocated for 40 years, there remains considerable confusion about the precise distinction between the schemes, particularly among the non-geological community, who also work on Quaternary sequences. In Europe, many of the terms in current use, perhaps surprisingly, do not have defined boundary- or unit-stratotypes. This problem has been recognised and steps are now being taken to define units formally through the work of the INQUA Subcommission on European Quaternary Stratigraphy. However, many fail to see the need for this, especially those who rely on geochronology, particularly radiocarbon, for correlation. For example, despite repeated attempts to propose a GSSP boundary stratotype for the base of the Holocene Series, Pleistocene – Holocene (Weichselian – Flandrian) boundary (Olausson 1982), only now is a universally acceptable boundary being sought (Walker et al. in press).

In languages other than English the situation is more confused. For example, in German the terms Glazial and Interglazial are used as equivalents of the English stage. Such an approach, on the face of it, seems expedient until one considers certain stages that have been correctly, formally-defined in the Netherlands’ Middle and Early Pleistocene, which are commonly used throughout Europe. Here the Bavelian Stage includes two interglacials and two glacials, likewise the Tiglian Stage comprises at least three interglacials and two glacials (de Jong 1988; Zagwijn 1992). Each of these interglacials are comparable in their characteristics to the last interglacial or Eemian which is a discrete stage, also defined in the Netherlands. In these cases workers have fallen back on the non-commital term complex. One example is the Saalian of Germany, originally defined as a glaciation, this chronostratigraphical stage includes at least one interglacial, as currently defined (Litt and Turner 1993). Attempts to circumvent the nomenclatural problem by defining a ‘Saalian Complex’ are a fudge at best but one that is occasioned by linguistic and long-term historical precedent, as much as by geological needs.

The original intention was that ‘cold’ or ‘warm’ or ‘temperate’ stages should represent the first-rank climate oscillations recognised, although it has since been realised that some, if not all, are internally complex. Subdivision of these stages into substages or zones was to be based, in the case of temperate stages, on biostratigraphy, and in the case of cold stages principally on lithostratigraphy. Within the range of radiocarbon dating (c. 30 ka) the most satisfactory form of sub-division is frequently that based on radiocarbon years (cf. Shotton and West 1969). However, high-resolution investigations, such as the ice-core investigations, have allowed the recognition of ever more climatic oscillations of decreasing intensity or wavelength within the first-rank time divisions. These events are stretching the ability of the stratigraphical terminology to cope with the escalating numbers of names they generate. Terms such as ‘event’, ‘oscillation’ or ‘phase’ are currently in use to refer to short or small-scale climatic events (‘sub-Milankovitch oscillations’: x ref). Clear hierarchical patterns are becoming blurred but perhaps this should be seen as a positive development since the system must reflect the need to classify events that are recognised. Moreover, as our ability to resolve smaller and smaller scale oscillations increases, a more detailed nomenclature will inevitably emerge.

Therefore for many Quaternary workers chrono- and climatostratigraphical terminology are interchangeable. Although realistically this situation is clearly unsatisfactory, because of the imprecision that it may bring to interregional and unltimately to global correlation, it is likely to continue for the foreseeable future. The long-term goal should be to clarify the situation by continuing to develop a formally-defined, chronostratigraphically – based system that is fully compatible with the rest of the geological column, supported by reliable geochronology.

References

American Commission on Stratigraphic Nomenclature 1961 Code of stratigraphic nomenclature. Bulletin of the American Association of Petroleum Geologists 45, 645-660.

Bowen, D.Q. 1978 Quaternary geology. Pergamon Press: Oxford.

De Jong, J. 1988 Climatic variability during the past three million years, as indicated by vegetational evolution in northwest Europe and with emphasis on data from The Netherlands. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B 318, 603-617.

Gibbard, P.L. & West, R.G. 2000. Quaternary chronostratigraphy: the nomenclature of terrestrial sequences. Boreas 29, 329-336.

Geikie, J. 1874 The great Ice Age and its relation to the antiquity of Man. W.Isbister: London.

Hedberg, H.D. 1976 International stratigraphic guide. J.Wiley & Sons: New York.

Jessen, K. and Milthers, V. 1928 Stratigraphical and palaeontological studies of interglacial freshwater deposits in Jutland and north-west Germany. Danmarks Geologisk Undersøgelse, II Raekke, No. 48.

Litt, Th. and Turner, C. 1993 Arbeitserbgenisse der Subkommission für Europäische Quartärstratigraphie: Die Saalesequenz in der Typusregion (Berichte der SEQS 10) Eiszeitalter und Gegenwart 43, 125-128.

Lüttig, G. 1965. Interglacial and interstadial periods. Journal of Geology, 73, 579-591.

Lowe, J.J. & Walker, M.J.C. 1997: Reconstructing Quaternary environments. 446pp. Longmans, London.

Mangerud, J., Andersen, S.Th., Berglund, B.E. and Donner, J.J. 1974 Quaternary stratigraphy of Norden, a proposal for teminology and classification. Boreas 3, 109-128.

Michel, J.-P., Fairbridge, R.W. & Carpenter, M.S.N. 1997 Dictionnaire des Sciences de la Terre. Masson, Paris & J.Wiley & Sons, Chichester 3e edition, 346pp.

Mitchell, G.F., Penny, L.F., Shotton, F.W. & West, R.G. 1973 A correlation of the Quaternary deposits of the British Isles. Geological Society of London, Special Report 4, 99p.

North American Commission on Stratigraphic Nomenclature. 1983 North American stratigraphic code. American Association of Petroleum Geologists Bulletin, 67, 841-875.

Nystuen, J.P. (ed.) 1986 Regler og råd for navnsetting av geologiske enheter i Norge. Norsk Geologisk Tidsskrift 66, supplement 1, 96p.

Olausson, E. (ed.) 1982: The Pleistocene / Holocene boundary in south-western Sweden. Sveriges Geologiska Undersökning C794

Penck, A. & Brückner, E. 1901-9 Die Alpen im Eiszeitalter. Taunitz: Leipzig 1199pp.

Salvador, A. 1994 International stratigraphic guide. second edition. International Union of Geological Sciences and Geological Society of America 214 pp.

Shotton, F.W. & West, R.G. 1969 Stratigraphical table of the British Quaternary. Appendix B1. In: George, T.N., Harland, W.B., Ager, D.V., Ball, H.W., Blow, H.W., Casey, R., Holland, C.H., Hughes, N.F., Kellaway, G.A., Kent, P.E., Ramsbottom, W.H.C., Stubblefield, J. & Woodland, A.W. Recommendations on stratigraphical usage. Proceedings of the Geological Society of London 165, 155-157.

Suggate,R.P., 1974 When did the Last Interglacial end? Quaternary Research, 4, 246-252.

Turner, C. & West, R.G. 1968 The subdivision and zonation of interglacial periods. Eiszeitalter und Gegenwart 19, 93-101.

Suggate, R.P. & West, R.G. 1969 Stratigraphic nomenclature and subdivision in the Quaternary. Working group for Stratigraphic Nomenclature, INQUA Commission for Stratigraphy (unpublished discussion document).

Walker, M., Johnsen, S., Steffensen, J.-P., Gibbard, P., Hoek, W., Low, J., Andrews, J., Cwynar, L., Hughen, K., Kershaw, P., Kromer, B., Litt, Th., Nakagawa, T., Newnham, R., & Schwander, J. in press A proposal for the Global Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) and Global Standard Stratigraphic Age (GSSA) for the base of the Holocene Series/Epoch (Quaternary System/Period). Episodes.

West, R.G. 1977 Pleistocene geology and biology second edition Longmans: London.

West, R.G. 1984 Interglacial, interstadial and oxygen isotope stages. Dissertationes Botaniceae 72, 345-357.

Zagwijn, W.H. 1992 The beginning of the Ice Age in Europe and its major subdivisions. Quaternary Science Reviews 11, 583-591.